Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Silence is the sound of the earth.

Silence does not need you to interrupt it.

She lived on an island formed 20,000 years ago by a moving wall of ice.

The day is long,she once wrote.It flirts with nothingness.

It always does.The clock in her kitchen read, as it has for many years now, 9:42.

She pulled long strands of brown hair off her furniture, a nuisance.

She took out a pair of kitchen scissors and cut the rest off her head.

The days were diminishing, but they always are.

She wrote new poems that felt like the old poems and rejected them.

When she was too sick to read, she watched documentaries.

Jorie Graham claims she doesnt know what silence she is breaking.

But Im telling you now, the silence has time in it.

It is a nakedness from which story will not appear to save you.

In which to hear itself.

I had hoped to escape.

To form one lucid

unassailable

thought.

It did not matter

about what.It just needs to be, to be

shapely and true.

The stories have their own trajectory, broken free of the life that inspired them.

If you open yourself up and look at a Goya, it could kill you, she once said.

That was what it was like.

When Jorie Pepperwas a toddler she lived in a small apartment in Rome that smelled of turpentine and lemons.

Money was scarce and the nation lately devastated by not one but two wars.

Beverly, painting in the living room, left to fetch something.

Jorie was 3 years old looking at the realist scene her mother had rendered mountains and people and animals.

Jorie, alone for a moment, placed her finger in a swirl of brilliant oil.

She traced wet loops on the canvas as her mother walked back in.

Jorie had never seen her mother lose her temper before; she would never see her lose it again.

Beverly picked up her daughter and threw her across the room.

From his office Jories father came running.

That was not what had been communicated at all.

I understood something there, she says now.

Can you hear it?

Beverly once said to her young daughter, standing in a field.

asked Jorie, alarmed.

The pull of the earth.

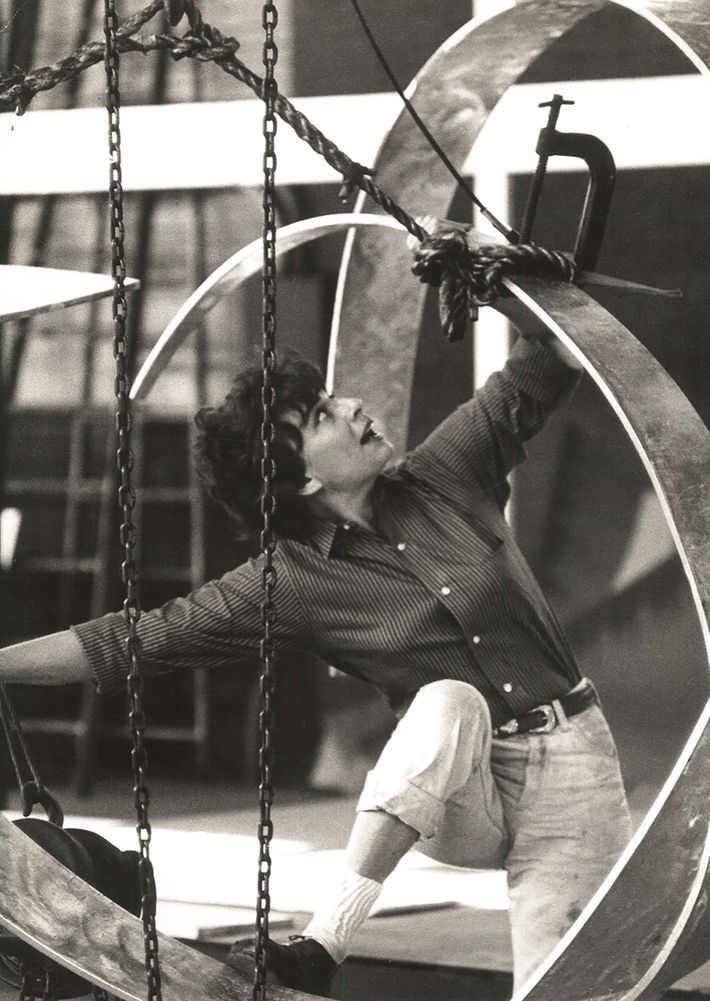

Beverly Pepper claimed to be able to hear it at its center, its molten iron core.

Jorie thought she was mad, though it was not a madness one could dismiss.

Standing next to her was like standing next to a divinity, a force.

Beverly Pepper loved ice cream, vodka, and baseball.

She was having some kind of crisis and took 10-year-old Jorie on a six-month tour of the world.

Beverly Pepper the sculptor called her daughter in from playing to hold some metal as she welded.

The sparks were cold.

In Rome, Jorie played hide-and-seek in medieval churches and realized only later that the sun had set.

She was a good hider.

Waiting to be found.

Thats a sacrament, he would say, the Eucharist.

Beverly Pepper would become, Jorie says, very Jewish in a Catholic church.

That Piero is not one of his great ones and let me tell you why, she would say.

Beverly, said Jories father, were in the middle of the Mass.

Perhaps it was sacred to someone, but it was also installation art, all of it.

The financial situation, until Jorie was in her teens, was at any given moment potentially catastrophic.

Its scary to have someone who is both an improviser and a perfectionist, Graham says.

Thats a hard thing to have as a mother.

You dont know what the rules are.

Beverly could turn her perfectionism on others.

Im not your sculpture!

Lately, she has taken to asking people when they think the sun will set.

They give the wildest answers!

she says, her voice bright with astonishment.

Six-thirty, they say.

No, its 4:34. beckoning the mind back to now.

The technology is fixing us into the absolute present, she says.

The internet beckons into a flat now, a constant attending to, a well of insistent digital need.

There is not space for the mind to build a picture of people who do not yet exist.

Here was a poetry unconcerned with character, fighting to escape the bounds of personality.

He knows hes trapped spiritually.

You cant be trapped aesthetically and not also be trapped spiritually.

If you cant move forward, youve been hunted into a corner, even if youre the hunter.

There was Jackson Pollock.

He does the drip paintings, and everybody loves that.

And then he wants to change, and he actually tries to reintroduce figuration into his abstraction.

But hes the guy whos not supposed to do that.

He self-destructs not long after.

I always thought they didnt want him to change.

They dont want you to change.

Jorie Pepper married Bill Graham and enrolled in the Iowa Writers Workshop.

He was never comfortable with her work; she had to choose between him and the poetry.

She did not choose him.

She next married James Galvin.

They lived very visibly in Iowa City, emanating the air of writerliness students came from all quarters seeking.

Students describe leaving her office hours crying with gratitude, the sense of having been understood.

It was all one could do to keep up.

A mind like quicksilver, in the words of former student and acclaimed poet Robyn Schiff.

I see what you mean now.She walked home barefoot to feel the grass under her feet.

She was playful in the way of someone unafraid.

Heavily pregnant, Jorie went to Emily Dickinsons grave.

She approached the gravestone; no answers came.

She walked to Emilys stately home, yellow with green shutters.

She just needed to see the space where Emily worked; she would know something then.

Through the gate, at the top of the steps, three women answered the door.

Three women, in Jories line of work, are The Fates.

She did not have an appointment and so The Fates told her she could not come in.

kindly, she said, I just need to see her room.

She needed to see where this woman had worked, where she wrote.

She began to cry.

The women let her go to Emily Dickinsons room.

Her desk was not there.

It was on loan, The Fates said, to Harvard.

She named the baby Emily.

You have a child in your arms who you know is mortal, she told a friend.

She had thrust someone into time.

The working artists daughter had a daughter.

Nothing is ever big enough, she said.

She cut into train cars.

She transformed wide swaths of land with towers and amphitheaters, work that followed the contours of the earth.

As an adult, Graham began to notice in her mother a nervousness born of insecurity.

Beverly Pepper was the only woman in the room, in the studio, in the factory.

Sometimes, in public, a kind of mid-Atlantic accent crept into her speech.

She got up and removed herself from the New York art world.

Emily was raised in her mothers office as her mother had been raised in Beverlys studio.

Jorie transformed a broom and wool sock into a horse.

Jorie took a beat.

Her explanation began with the French Revolution.

Emily attended public school in Iowa City.

Theyve got the answer inside them.

Youre now saying:You dont have to have it inside you.

You just punch it into this machine, it has it inside it.

At a dinner party at the home of Mark Strand, she met Peter Sacks.

Her success was also his.

She and Sacks would both ascend to Harvard.

She published book after book, eight of them, during this marriage.

When she criticized his work, he took it with grace.

During the course of Jorie Grahams workshop, Gunn was struck down with debilitating depression.

Graham called her in bed.

Im in bed, Gunn said.

I cant get out of bed.

What if you dont write about the depression, said Graham.

What if you write from the predicament of it.

Amanda considered this:the predicament of it.Youre in bed, said Graham.

You cant get out of bed.

Whats in the bed?

She was so frugal her barely working refrigerator spoiled her food and made her sick.

How many people have a Jorie Graham writing about them?

Beverly said looking up from the notebook where she was still, at 97, sketching coiled sculptural forms.

Why arent I in more of your poems?

The truth was that Jorie didnt feel a pull to her mothers art.

They werent asking the same questions.

She was just Mom, always working.

Jorie could sense her mother roaming the earth, searching for sites for works that were not yet settled.

There were three sets of 40-foot Cor-Ten columns, of which two had been placed.

As Beverly became disoriented, among her last words to Jorie were put them in desert light.

Jorie watched the woman leave the room and return with others.

She watched her mothers body as it was undressed and bathed.

It was on the Nest app that she watched her mother die.

People had alwaysmisunderstood the nature of Jorie Grahams privilege.

It wasnt money, of which, for a long time, there had been none.

Does this art form matter?

These questions just were not posed.

This was an ethic but also an inheritance.

These tasks filled her with anxiety, at every turn a problem.

COVID kept her in the house in Marthas Vineyard.

She was not writing; she had not yet become the person who could write the next book.

There must be more.

The more had not revealed itself.

He dragged himself on his elbows up the shore for 40 minutes.

It was winter, the temperature in the low 40s; no one came.

The sky had never seemed so big.

Several times he passed out and came to again.

He screamed; no one heard.

He expected to die.

Half a mile up the shore, a dog ran up to him, followed by its owner.

For 30 days, COVID protocol kept them apart.

A place was found for the columns, now known as the Stanford Columns.

Something was happening to Grahams memory of her mother.

With time, she became memories and stories.

With more time, she became others stories.

She became what she left: the art.

They made youfeelthe weight, the gravity under which they bore up.

When finally erected, the Stanford Columns would convey not a sense of historical but of geological time.

Eleven months after her husbands fall, an acupuncturist suggested she get a pelvic ultrasound.

She first heard the oncologists words asserious endometrial cancer.The word, though, wasserous,which was worse.

During her previous cancer, the doctor had spoken of beingbeyondscans.

They spoke now only of beingbetweenthem.

The surveillance would endure.

There would be no next book, she assumed now.

It was surprising to her, her inability to make peace with the diminishing days.

Despair loomed, a closing in, and it did not promise a new music.

The doctors told her to walk to mitigate what might otherwise be irreversible nerve damage.

She walked and she imagined.

She was conscious of the feeling of each muscle of her feet on the surface of the earth.

The current that sparks a dividing cell.

She did feel it.

She felt it, coursing up from the earth through the tips of her fingers.

She could cast herself into it and write back to the present.

The silence, she saw when the music finally came, was stronger now.

She did not have the luxury of the line unfurling across the page.

She would need tohammer back with strong, short beats.

Grief is a form

which can shape this

if you want a shape.

But it’s possible for you to also sit here

a long time

without ever again

needing a shape.

She called the bookTo 2040and, though it felt somehow unfinished, sent it off in July.

The clock in the kitchen read 9:42.

It was late summer now on the island, and it would not rain.

Its gone to Nantucket, people said of each storm.

Its gone to the mainland.

The Vineyard stayed dry through lightning.

When the rain finally broke, she walked outside and sat on a low stone wall.

What time will the sun set today?

What is it you are doing to justify interrupting the sound of the earth?

The light turned to darkness.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.