Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

Youll find no comfortin exotica here.

No kaleidoscopic weddings to reel a reader in.

No stern fathers, no dishes to remind an exile of home, no careful arranging of marriages.

There are, however, a lot of coconuts and at least one mango.

The most notable mango-eating scene directly precedes a gory murder.

Its Athena who tells us the story.

Yet Vara has not exactly made this book an easy read.

If youre a person like us a cripple, an untouchable youve got to make them afraid of you.

Youve got to place yourself above them however you could, the man tells King.

Then he insists the boy touch the stump of his severed leg.

Vara tells us the stump is smooth, hard, hot.

King begs to stop.

King feels ill at that moment.

I had felt ill myself, during earlier scenes.

Vara does not emphasize the photogenic side of life.

The suburban bohemia that can seem to define the American novel is nowhere to be found here.

The only community is a fractured one.

And to what end?

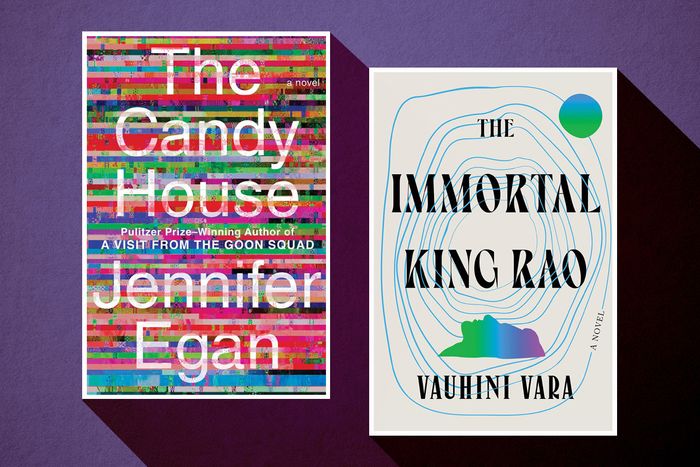

InThe Immortal King Rao, Vara constructs a world designed by man and woman.

(And offers up a useful storytelling hack; Athena narrates Kings life via access to his memories.

)Yet King is a complex figure, neither villain nor hero.

But if he hadnt done it, someone else would have …

If we had killed him, someone else would have become CEO in his place.

She is an outlier.

Western public intellectuals of Hindu parentage are more likely to be Brahman, and the names give it away.

Here is a truly American novel: Steve Jobs, but untouchable.

Elon Musk, but brown.

Some of the most compelling of the novels passages betray a journalists sense of the world.

But the internet ofImmortal King Raois also one mapped by a poet.

Vara is forever aware of the costs of technology, of the hidden world behind the public one.

This world teems with small moments the cadence of romance, the missteps of an immigrant.

Althoughthe title character is a man, women are chief among the storytellers and meaning-makers.

Theres the narrator, Athena.

Theres the Rebel Elemen Ex, with whom Athena shares an uncanny connection.

Margaret wants nothing to do with childbirth, with motherhood.

She uses King hes pliant because she knows the world will not accept her force.

Shes a puppet master, but she loves him.

Varas novel works in gyroscopic ways, world-building in a circular progression.

Every child is arguably forever in touch with the parent of the past.

Afterward, she reflects on the feeling the scene leaves her with.

She realizes she loves her father despite herself.

Vara is something of an old hand at this marriage of form and function.

Last summer, she published a story inThe Believertitled Ghosts.

Grief can render a griever mute.

Vara found a way to tell the story through the filling-in capabilities of a sophisticated writing bot called GPT-3.

The piece is surprising; it reads so alive.

The Immortal King Raotoo thrums with a pulse.

Born in unusual circumstances, Athena faces an age-old conundrum writ large.

How do you break off from the larger-than-life parent?

In Jennifer Egans novelThe Candy House, a world that can seem twinned to Varas unfurls.

The Candy Houseis dizzying,in scope and achievement.

Egan telescopes in on more than a dozen characters with an unnerving mastery.

The rakish record executive Lou Kline is seen through the eyes of his daughters.

Sasha Blake has traded her kleptomania for a quiet, celebrated life as a sculptor in the desert.

(And to be struck by novelistic trends: The names Athena and Hollander appear in both books.)

At times, Egans approach feels almost too masterful.

Egan moves her players around in exhilarating ways.

Two warring, paranoid neighbors form a delicate friendship in the background of other stories.

Egans brilliance at constructing vignettes is layered into more dimensionality here, thanks to the futuristic window dressing.

But ultimately these are old, small tales.

People are born, fall in love, marry, have children, die.

The technology adds a layer of possibility, of complication: Characters can now see what a parent saw.

They can see what happened on that day long ago when a friend died.

Perhaps they can see life as a novelist does.

wonders the mother of Ames Hollander in a finely wrought final chapter titled Middle Son.

There are so many boys in the world.

From a distance they look alike even to her, especially in uniform.

Horror here ties to human quandaries, not ones invented by technocrats.

Social injustices are dealt with poetically, even playfully.

Her behavior is incomprehensible to those around her.

She looks very much like a bad mother, a bad wife.

For some people, of course, things really dont change, no matter the conditions of the world.

Both authors offer the suggestive existence of rebels.

Egan never shows us her eluders, though; we never go with them into the wilderness.

Perhaps its a trap that feels like protection.