The Fraudis out now from Penguin Press.

Save this article to read it later.

Find this story in your accountsSaved for Latersection.

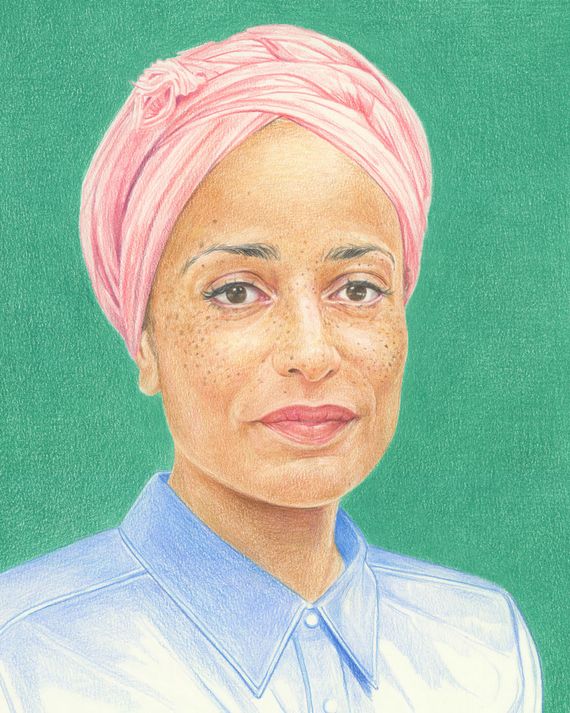

Zadie Smiths first book,White Teeth,was the English comic novel on bath salts.

Is Britishness cream tea and the queen?

asked the New YorkTimes.Or curry and Zadie Smith?

But Smith also had her critics.

For Wood, a passionate defender of the realist novel, this meant thatWhite Teethlacked moral seriousness.

Smith has apparently concluded thatWhite Teeths greatest strength, its audacious unreality, was in fact its fatal flaw.

Today, she is firmly within the realist camp despite her recurring feints at departure.

This is Smith: radical for the sake of tradition.

Was this what the admirable Mrs Lewes felt as she worked?

wonders our budding lady novelist as she prepares to write.

More than ever, Smith is asking herself the same question.

WithThe Fraud,Smith delivers her most passionate defense of this idea to date.

Whether it persuades is another matter.

Years of living witha novelist have made Mrs. Touchet suspicious of the whole breed.

God preserve me from that tragic indulgence, that useless vanity, that blindness!

But one never seriously supposes Smith has lost her faith in the novel.

Eliza must have a change of heart.

But Bogle, formerly a valet to Sir Rogers uncle, is something different.

Desperately curious, Eliza poses as a journalist and convinces Bogle to tell her everything.

But to her astonishment, it opened inwards.

She had been standing inside the very thing shed been looking for.

One need not believe Bogle to find himbelievable,the way a character in a good novel is believable.

He is one of Forsters likely people, fully, unfathomably alive.

Stories of human beings, struggling, suffering, deluding others and themselves.

In fact, there is one novel Eliza likes very much.

As Eliza opens herself to Bogle, this roar will begin to split her ears.

Just who does she think she is?

So perhapsThe Fraudexpresses an anxiety about the novel equal to its defense of it.

But for Smith, the inevitable fraudulence of the novel is precisely what gives it its moral urgency.

Like Dorothea inMiddlemarch,she is reaching imperfectly toward the fullest truth, the least partial good.

Who does Eliza think she is?

Well, a person.

Doubtless, many would no longer stand by what they said in the afterglow of 2008.

This humanist impulse has made for some perennial wrongheadedness.

She is Zadie Smith.

But, for her, negative capability gently dissolves the specific contents of whatever consciousness birthed it.

This is a good point.

But one should never trust an argument that depends on the anonymous defenestration of undergraduates.

This is a willful misunderstanding.

Of course Woolfs racismisinteresting to those whom Smith calls, with not enough irony, the youngs.

material struggles around, say, wealth inequality or prison abolition.

But this too is a political position.

For Smith, the novel is just such an experiment in thinking beyond our closely held identities.

Its true that many bad novels have substituted ideology for interest.

Its equally true that Smith envisions the novel as a little liberal machine for making more little liberals.

We hope for a literature and a society!

that recognizes the somebody in everybody.

But they are all gums, and no white teeth.

SupposeZadie Smith is right.

How does fiction arouse our sympathies?

This makes sense: We are moved by Hamletsfeelingfor poor Yorick, not by Yorick himself.

Perhaps we will have better luck with one of the blind.

Over a century of readers has been moved by this image.

So how is the author to get out of the way?

Did he think her a vampire?

she writes inThe Fraud,adopting Elizas anxiety about Bogle as her own.

She only wanted to know what could be known of other people!

The second sentence is classic free indirect, a clear back-shifting of the contents of Bogles consciousness.

But that gold and russet forest whose thought is this?

Which one should I pity?

(The closest she came was the affecting portrait of a crumbling marriage inOn Beauty.)

But what moved us was the reverse: These people had all beenher.

I will simply never get them alone.

But the humanists mistake is to suppose that politics is just lots and lots of ethics.

In this sense, fiction has always been an exercise in political consciousness.

Not for nothing do we call it the third person.

The author ofWhite Teethknew this.

And it was true that Smith sometimes wrote too blithely of people unlike herself.

(There was an Arab family that named all their sons Abdul.)

But Smiths characters did not lack humanity so much as she lacked a use for it.

Her eye was trained on a collectivity: the vibrant Willesden Green of her youth.

Accordingly, Smith never asked too much of her unlikely people.

You could tell they had better things to do than be furniture in someones novel.

No one can stop you.

How might Smith have answered them?

So for her sake, let us look somewhere more morally serious.

This is a splendid notion.

The genius lies in knowing which ones they are.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.